Looking back on my eight days wandering around Myanmar’s two most famous archaeological sites, I realise that so much of what I would say about one is by reference to or in contrast with the other, I thought I’d write about them together.

Bagan tends to be regarded as THE must-visit site in Myanmar. Even Yangon’s Shwedagon Pagoda and Inle Lake, with its leg-rowing fishermen, take a back seat to this extraordinary 40 square mile area and its two/three/four/ten thousand temples, pagodas and monasteries (no two sources come up with the same number either of those constructed or of how many remain) from the eleventh to thirteenth centuries when Bagan (Pagan) was the capital of the Pagan Empire, the first kingdom to unify regions that would later constitute modern-day Myanmar.

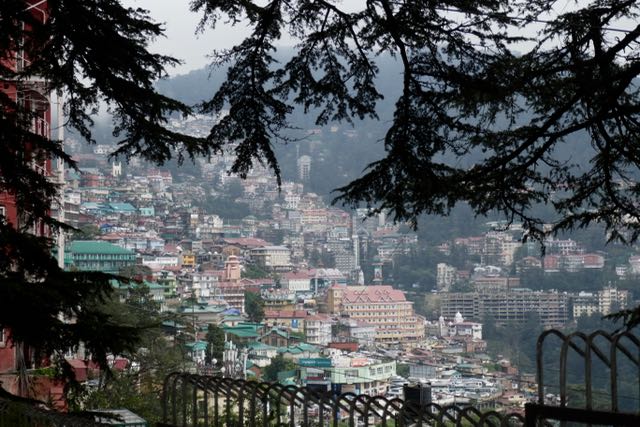

As for Mrauk U (pronounced “miao-oo” locally), only the cognoscenti, or so it appears, have heard of this former capital of the dominant naval and international trading nation of Arakan, and its slightly more modest collection of temples built in the fifteenth to eighteenth centuries.

Bagan is highly accessible, the Nyaung U airport at the eastern edge of the temple-littered Bagan plain receiving direct or tourist-route flights multiple times a day.

Mrauk U doesn’t (yet) have an airport. The only way to get there – if you don’t feel like 18-plus hours in a bus on winding roads – is to take the boat up from Sittwe, the state capital, having flown in from Yangon. The 4/5-hour boat trip is a lovely journey, though Sittwe itself has little to offer. It’s very much a working town; tourists aren’t anticipated or catered for. Hotels are basic, restaurants next to non-existent, and the most stunning building in town is the mosque, which is barricaded and crumbling, ever since the communal violence in 2012.

Bagan is touristily-sophisticated. Each of the key temples is marked by a row of stallholders selling more or less similar memorabilia, and a greater or lesser forest of waiting transportation, though in neither way does it rival Siem Reap or any of the major sites in India. So far at least, the Burmese are far less pushy than their counterparts. The neighbouring town-lettes of Nyaung U and New Bagan are littered with hotels, bike rental places, and information/onward-travel-booking kiosks, and Nyaung U boasts a street several blocks long known unofficially as “Restaurant Row”. Bangkok’s Khao San Road it is not, but it’s the most tourist-focussed stretch of road I’ve yet seen in Myanmar.

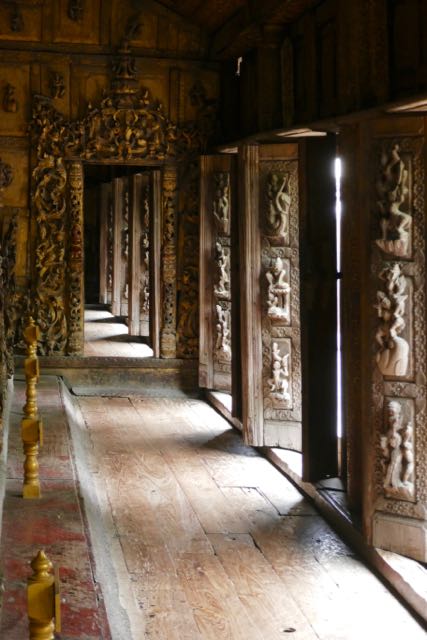

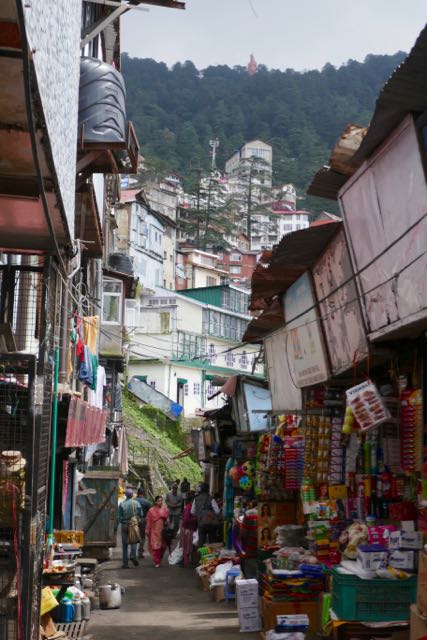

In Mrauk U, the only temple that has any accompanying touristiness is Shittaung Paya, the one place every (honest) foreigner must visit in order to pay the entrance fee for the whole site. Even here, I found far more locals and Burmese tourists than firangis. It’s as if Mrauk U hasn’t really woken up to the potential for international tourism, though its remoteness will continue to hamper its development in this regard and there’s no doubt that recent events, already affecting bookings in the rest of the country, will have clobbered tourism here in Rakhine state itself. Hotel options are limited, restaurants even more so, and there’s almost no ancillary services market. Even the tuk-tuks (here called “thoun bein”) seem shy in offering their taxi services. Firangis are unusual, stared at, giggled at (or with), English shyly practised by the more daring.

To explore Bagan requires transport. Even the walkaholic has to admit defeat here. With the government banning motorbike-taxis and thoun bein from the temple area, the tourist’s choices are a horse-and-cart, DIY bicycle or “e-bike” (a battery-fuelled moped), or, to the extent that it can make it through the sandiness of many of the tracks, a taxi.

The majority of Mrauk U’s main temples are walkable. Yes, you clock up some distance and the temperature may not be everyone’s cup of tea, but it’s manageable and hugely rewarding. One day I was the only firangi I saw, and I had stretches of time where I didn’t see another soul. In Bagan I met a German lady who’d last visited the country 21 years’ ago. I wonder now whether the Bagan she saw then was like the Mrauk U of today, and envy her that Bagan.

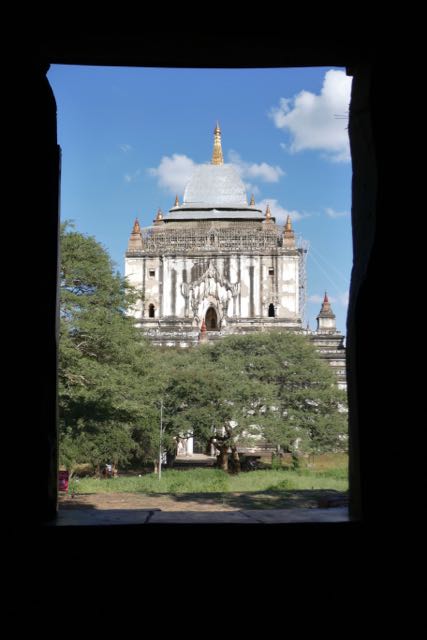

The majority of Bagan’s temples are built of a rich red brick with a smattering of white-washing and gold around; with only one or two exceptions, Mrauk U’s of a dark grey stone, and some so much more resemble defensive structures than religious buildings that they have been mistaken for forts.

The Bagan plain has several settlements around it, but, with the exception of a couple of temples in Nyaung U and New Bagan, there is only a very limited amount human habitation near the majority of temples. The village that had grown up around Old Bagan’s monuments was forcibly relocated a few kilometres down the road in 1990, tourist hotels put up in its place as the government realised the power of tourism to bring in much-needed hard currency. The effect is therefore that the vast majority of the monuments are insulated from the real world. Yes, the Burmese who visit them often pray there, but, for the most part, these are not temples that are part of everyday life.

In Mrauk U, on the other hand, there is a lovely immediacy and relevance to the temples. They are in the middle of paddy fields, up the hill from the nearby village, part of the furniture, as it were, and many have their own attendant monks and/or nuns: part of the here-and-now.

None of this is meant as a criticism of either place: they are simply very different, and I loved my time in each, even if I did feel as if I were clocking up an eye-watering number of temples each day. (I asked a friend recently for her recommendations for my weekend visa-run in Singapore – Myanmar only gives tourists 28-day visas – and she mentioned an area where there is a mosque, a Hindu temple and a church in close proximity. Wow, a religious site that isn’t Buddhist: that’d have an air of novelty, I thought.)

In Bagan, THE thing to do is to go for a hot air balloon ride over the monuments at dawn. Any later in the day and the temperature in this, one of the hottest parts of the country, makes flying infinitely less predictable, so the three companies operating balloons have decided to focus on the almost-guaranteed dawn departure. I was afraid I’d left it too late. The Balloons Over Bagan website said they had no availability until much later on in November. I was kicking myself: I’d planned my Bagan dates sufficiently far ahead that I could have booked it earlier had I only thought. With low expectations – even congratulating myself on the money I wouldn’t therefore be spending (it’s not cheap, of course) – I went into the “BOB” office the afternoon I arrived in Nyaung U. And ten minutes later came out with a booking for three days’ hence. All my virtuous thoughts about the unspent dollars went out the window; I had a happy grin meeting round the back of my head.

Just around the corner, Konaing (pronounced ko-nai) and his brother, Gotek, were to be the immediate beneficiaries of my bonhomie. “Taxi? Horse cart?” they asked me in unison. I paused. Well, I didn’t fancy cycling around the temples given the dusty, slippery condition of the tracks (and my ability to become, um, geographically challenged), and I had already been thinking that, in contrast to my piousness at Inwa, I would like to look at the horse-and-cart option here. And there was the possibility of a half-day trip to nearby Mount Popa for which a vehicle would be required. After a little discussion with the two men, and a short interview with Mu-Mu, the equine end of the partnership – you can tell a lot from the way a man treats his animals, and Mu-Mu was in good condition, to my relief – we had a deal. Konaing and Mu-Mu would take me round the temples the next day, and, all things being equal, Gotek would drive me to and from Mount Popa the day after. (I asked Konaing whether he’d be driving, and he said that, while he does have a driving licence, “I do not like speed”.)

And so I found myself on the first of what were to be three new-to-me forms of transport in as many days. On the Tuesday, Konaing and Mu-Mu took me around the temples of the South Plain, the Myinkaba area and the North Plain. On the Thursday morning, I prised myself out of bed at 4.30am for my first (and, let’s face it, probably only) hot air balloon flight over the whole area. There’s a government-imposed restriction on flying over the Old Bagan temples, but, in fact, the key ones are so large that they’re eminently visible when you’re flying over the east and south of the plains. And on the Thursday afternoon, I braved the e-bike thing… and resolved to have a moped/scooter lesson when I got home. A right-hand-operated accelerator is definitely not intuitive, I decided, as I picked myself up out of the dirt having failed to switch the engine off before turning the bike around for a temple I’d just missed. (And some of my friends were thinking the ballooning was going to be the scary part!)

The day trotting around in a horse-and-cart was luxuriously relaxing. While I admit it’s not the most comfortable form of transport – Konaing’s cart is lined with foam mattresses, but the height of the canopy doesn’t anticipate European inches – it was wonderful to be pottering along so gently and quietly. Mu-Mu didn’t bat an ear or miss a step, no matter what other transport might have been doing, even on the short stretch that is as close as Bagan comes to dual carriageway, with its occasional buses. I made sure to thank her each time I dismounted for a temple – all, um, fifteen, I think, that I visited that day – and to ask her if she was all right to continue each time I re-mounted. Konaing seemed touched at this, and he was clearly very considerate of her himself, making sure to rest her in the shade and imposing a lunch stop that was primarily for her benefit rather than ours.

The hot air balloon ride was phenomenal. There are some experiences for which it’s just worth paying the money. Trekking with gorillas in Rwanda was one, flying over the Nazca Lines in Peru was another, and this was definitely a third. Understandably, it’s an almost military operation, with 21 balloons between the three companies all being prepared for take-off from the same area at the same time. Battalions of minibuses collect the punters from a 7-km radius, depositing each busload to the correct campsite where hot coffee and shortbread is on hand (I was afraid, when I saw yet another busload join our group, that, in having a second cup of coffee, I might have dented their rations, but clearly serious caffeine needs are anticipated). Safety briefings are given by each pilot to their balloon-load, and then the acres of lifeless silk are slowly inflated by massive fans, each balloon remaining tethered to a nearby minibus. Everyone on the team of a dozen or so per balloon knows their role to the last inch. Ropes are tugged, silk coaxed, and even the inside of the inflating balloon is checked to ensure all is in order there. At a certain point the burners flare, and we feel an unspoken competitiveness with the other balloons: is ours going to be first? Which one’s lagging behind? Once the balloon is vertical and the signal is given, we clamber aboard. Final checks go on between pilot and ground crew with much radio liaison, and then suddenly we’re waving to the ground crew. Jokingly (we hope), the crew call “See you tomorrow”, when, in fact, they are each going to be keeping in close contact with our pilot to coordinate the minibus and tractor getting to the right landing zone. Ours was a day of “light and variable winds” and I gather our crew had their work cut out for them as Chris-from-southwest-London (most of the pilots are British), told them first one site, then a second, and then a third.

By the time we took off, the sun was just at the horizon. We’d all gone prepared with extra layers, but the heat from the burners, although they were only sporadically fired, was enough to keep us warm. The views were simply magical. When the burners weren’t roaring and the chatty Germans in the far end of the basket drew breath (our basket had five sections, the middle one being Chris’s “office”, with each of the other sections able to accommodate up to four people, although we were only 14 passengers in total), it was wonderfully tranquil. Somewhat randomly, as it seemed to us, Chris took the balloon up and down, searching for the most helpful wind on this slightly challenging day. At one point, I thought we were going to scrape the top of the palm trees. At other times, we had an endless view across the Irrawaddy to the north and west, and over to the extinct volcano behind Mount Popa, Taung Ma-gyi or Mother Mountain, to the south. But then we flew over a farmer leading his oxen and plough, a couple of women hunkered down on their haunches working in the field beside him, and I suddenly felt sickened. In this, one of the poorest countries in Asia, I had paid what was likely the best part of their annual income for a two-hour experience. I could only rationalise it on the basis that, overall, tourism is essential to the area, bringing in much-needed income that flows down through all levels, even to our farmer in the fields as he sells his crops to nearby restaurants. But it was still an uncomfortable realisation.

Back on the ground and after a suitable snooze to recover from the painfully early start, I bit the bullet on the e-bike experience. Once I’d got going, I found it a lovely way to travel. Almost silent, yet reasonably speedy. But starting and stopping remained challenging, even after a second half-day on board the next day. These small technicalities to one side, it was the perfect way to travel around to fill in the temple gaps, taking me to Old Bagan (where I wimped out and parked the bike by the city gates, electing to go around temples on foot) and further afield to the Myinkaba and New Bagan temples. My last stop was Mahabodhi Paya, modelled on its namesake in India which commemorates the spot where the Buddha attained enlightenment. I’m not sure I’d attained much beyond a couple of hundred photographs, a scraped calf and a bruised hip, but I was happy, and, after returning my steed to its stable, went off to commemorate my achievements with a large cold beer at the delightful social enterprise restaurant, Sonan.

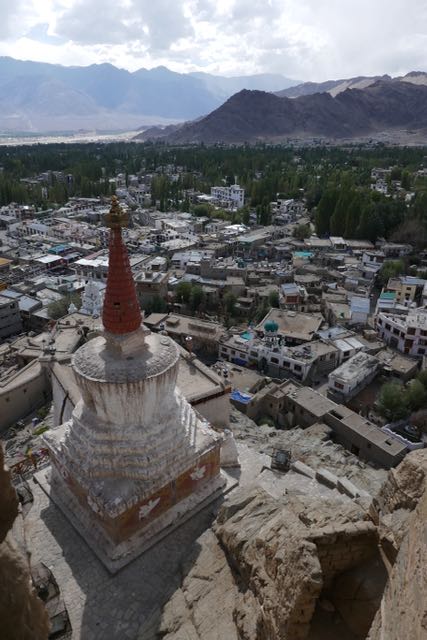

Slightly less than two days’ later, I set out again, on foot this time, to explore the temples of Mrauk U. Here the landscape is hilly, and practically every lump of ground is crowned by a stupa of some description. The dark grey stone and imposing designs make the temples here impressive rather than picturesque, but their immediacy, their lack of tourist paraphernalia appealed to me enormously. On my second day, when I was exploring temples further afield, I frequently found myself on my own, not even a farmer in a nearby paddy-field or gang of kids tagging along. The audio backdrop was pure nature, timeless. It may have been a tad on the warm side – 32C with xx% humidity, “feels like 38C” my phone kindly informed me – but I was relishing every minute of it…

…until I got to the Shwetaung Paya. I guess I should have believed the Book when it said “it’s accessed by a few trails largely lost under thick vegetation”. That’s putting it mildly. The uncharacteristically golden stupa was clearly visible at the top of the hill, so I stopped to ask a monk who was pottering outside what was clearly “lower” Shwetaung Paya the way up. He pointed vaguely behind a grazing almost-albino gelding, and sure enough, there was the bottom of the track. Which was about as visible as it ever got. Not to be deterred, I scrambled upwards, looking each time for the least thick growth through which to plough my way. I came across a second track that approached from the other side of the ridge, so made a note to myself: look for the yellow flower (which I’d just passed), and ignore the red (which I could see in front of me). Woe betide me if a flower-picking supplicant appeared while I was up top. At one point, I had to scramble up a slope, grabbing onto whatever branch or undergrowth didn’t immediately give way. And yet the Paya gleamed above me, daring me to make it the whole way up. More by luck than judgment, I popped out at the foot of overgrown stone steps to be greeted by a pair of chinthe, the Burmese lion-like creatures that often guard temple entrances. I swore some very un-Buddhist things at them, and the golden stupa beyond. But the views were fabulous, and after half a bottle of MAX, Myanmar’s answer to Fanta, I was prepared to enjoy them; they had been worth the climb. Yet, cautious of the perils of gravity on the unwary, I messaged two of my siblings to let them know where I was and what to do if they didn’t hear from me after a certain period of time. Extraordinary as it was, even here, in the back of the back of beyond, I had a good mobile signal. The travel gods were with me, however, and I made it safely back down the hill with only a few scratches.

After so much of the other-worldly, it was time to return to somewhat more prosaic considerations: getting back to Yangon and thence to Singapore for the weekend. Myanmar only allows tourists 28 days on their visas, and I would need a new one if I were to continue my adventures in the south.