It’s not on everyone’s travel list. In the West, the word alone conjures up images of military coups and political assassinations – Benazir Bhutto’s may be the most recent and most famous, but Pakistan’s been at this since it was four years old. Then there’s Abbottabad, the last refuge of Osama bin Laden; support for the Afghan Taliban; the on/off nuclear standoff with India; the ongoing dispute over Kashmir.

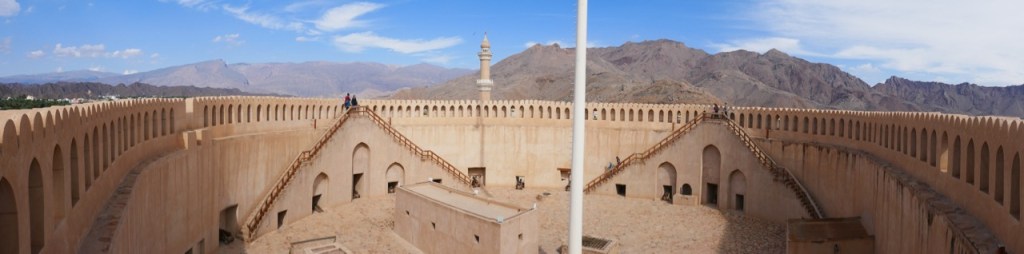

And it wasn’t really on my list either until I met Barb in Oman a few years’ ago and heard tales of her month-long trip there earlier that autumn. Until I saw her pictures.

“Spiky mountains,” said my brother dismissively, pushing me for a reason for my latest trip. “Haven’t you had your fill of spiky mountains?”

Clearly not.

On my return, there were the usual questions, “So how was your trip? What was it like?”. How do you condense a new country-experience without your audience checking their watches? When it ranged from exploring on my own to the ebullient and crowded celebrations of a pagan festival; from the plains of the Punjab to yes, some very spiky mountains (and these were only the fringes of the Hindu Kush); from Gandhara to the Mughal empire, and the all-too-recent agonies of Partition?

In a word: friendly.

The imposing Pakistani Rangers at the Wagah border crossing with their beaming “Welcome to Pakistan” as they opened the high iron gates just wide enough for me and my luggage cart to squeeze through.

On the overcrowded metro-bus in Lahore, a gaggle of young women counselling me with assured advice and posing tentative questions as the vehicle lurched along the overpass. Among them, the newly married Fatima. Enchanted to hear I’d visited her alma mater, Kinnaird College, earlier that morning on behalf of a reminiscing friend who’d worked there before Fatima was born, she insisted on negotiating and paying for my onward tuktuk to the Mughal tombs of Shahdara Bagh.

The street seller in Peshawar insisting on our trying his speciality kebabs – with two of us vegetarian, it was the ever-obliging Alex who stepped forward – yet refused all efforts at payment.

And, above all, the all-embracing warm hospitality of our hosts, welcoming us like family, and the people of the Kalash village of Balanguru when we joined them for their winter festival of Chaumos.

Our Swat Valley police escort’s formality melting away when the cameras appeared and our glamorous Terri asked for a selfie. At each district border, the old escort would wave us cheerfully on our way as the new one took up position.

But Pakistan wasn’t an instant love affair, I admit. Crossing over from Amristar was tiring, albeit less than 60km away, and my Lahori hotel abutted a major thoroughfare, which, with streetlights sporadic and pavements non-existent, did not seem close to any obvious dinner options. I find land borders exhilarating – the timelessness and raw exposure of walking between border posts, the unpredictability of the process (my papers must have been checked six or eight times on the Indian side, and a polio vaccine administered for no obvious reason) – but they’re not without a modicum of stress and a whole lot of waiting around, though there can be unexpected moments of humour. This time it was the Pakistan immigration official, who emerged from his office to say he was in the middle of his lunch; please could we give him half an hour? “No” wasn’t an option. The three of us – myself and two Pakistanis – sat down obediently.

The next morning, Lahore’s pollution and noise reminded me of India 25 years’ ago, and the prospect of a couple of days here seemed daunting. But my first stop, Kipling’s “Wonder House” (I was re-reading “Kim”) – albeit now a few doors further up the road – worked its magic. The Lahore Museum’s series of high-ceilinged cool halls feature displays of artifacts dating back to 7,000 BC, as well as comparatively more recent finds from the Indus River civilisation and the Gandharan empire. One of the Museum’s most notable pieces is the Fasting Siddhartha from the second century AD, but its emaciated form left me cold and somewhat revolted. Instead, I thrilled at the sight of the ancient Qur’ans, one being almost 1,500 years old, and many written in both Persian and Arabic, their glorious flowing calligraphy interwoven in different colours. Several school groups were visiting, little flocks of chattering uniforms, including a trio of be-phoned teenage girls who accosted me, giggling behind their niqabs, and politely firing questions in carefully poised English. It was tricky to know who had spoken, so my glance skittered around as I replied, and I was reminded – one of the lessons of covid – quite how much expression the eyes alone can convey.

Kim’s cannon is now sadly fenced off and stranded in the middle of six lanes of traffic. After all, the story goes that whoever controls the cannon controls the Punjab, so some degree of precaution would seem to be desirable. Having taken my life in my hands to cross the road, I ducked into the maze of narrow streets that comprises Anarkali Bazaar, and made my way towards the Walled City – where I found a Lahore I could love.

Strolling through the Bazaar, let alone the even narrower and winding streets within the Circular Road that protects the old town and innermost Walled City, is not for the faint-hearted. Traffic can approach from every direction, the “rules” of the road being more of a “guideline”, particularly in the minds of mopeds and motorbikes. But, if you stand for a moment – with your back against a wall for safety’s sake – and look around, it is hugely rewarding. No two buildings are the same. Old carved wooden balconies still cling to upper floors. Electric wires form a cat’s cradle of chaos not much above head-height. Domed cupolas and stone archways give a glamour belied by the building’s appearance at street-level. A wee boy sneaks a peak from between bamboo blinds two floors above. Stalls show specialisations that defy commercial logic: can one really make a living selling yellow HB pencils?

Within the Walled City’s imposing ramparts, a calm descends, traffic kept safely at bay. Here are two of the jewels of Lahore: the Fort with its welcome expanse of green parkland around and between imposing Mughal buildings in varying states of renovation; and the stunning Badshahi Mosque with its impressive, stepped approach leading up from the geometric formality of the Hazuri Bagh – where emperors would review their troops and hold court – to its grand red sandstone gateway. Apparently, its courtyard can hold around 60,000 people, which would dwarf Delhi’s Jama Masjid. That afternoon, there was just me, an earnest group of madrassah students, and a female cat overseeing her offspring’s explorations. Outside, I sat on the grass and drew breath, while a small convocation of eagles descended and pecked away at the ground nearby, seemingly oblivious to their surroundings.

On the far side of the old city, modern Pakistan makes a dramatic re-appearance, with the Eiffel Tower-esque Minar-e-Pakistan dominating the sprawling but well-kempt Greater Iqbal Park. It marks the place where, while European interest was focused elsewhere, the All-India Muslim League passed a resolution calling for the creation of an independent Pakistan, the first official demand for a two-state solution to the looming question of British India’s future. Muhammad Iqbal, a major figure in the Muslim League and the man behind the name – of the country and of the Park – is buried in the Hazuri Bagh, though access to his tomb was blocked off by restoration work when I was there.

As the sun began to set, I meandered back through the old city’s rabbit warrens, now bustling and lively with evening markets, and tripped over what may well now rate as my Mosque Of The Century, the Masjid Wazir Khan. Escaping the tarpaulin-covered alleyway where I’d been dazzled by the colour, sequins and mirrorwork of the clothing on display, I found myself looking up at a red sandstone minaret whose octagonal sides were punctuated by what, at first glance, appeared to be more of the same sparkling colourful fabrics I’d just been admiring. The Masjid’s tile panels are glorious, many outlined in gold and featuring, as far as I could see, every colour under the sun. The courtyard in front of the main entrance is a little below street level. In the evening, divans and tables are laid out and street sellers display their wares under the arches, making for an unexpectedly cosy and convivial setting. Of course, like much of what I would see in Lahore, it will be wonderful when the restoration is finished, but it was heartening to see so much work going into preserving the country’s heritage.

That evening, I treated myself to dinner on the top floor of the Haveli Restaurant on the aptly-named Food Street. This was Biryani With A View, a stunning outlook over the floodlit Fort and Badshahi Mosque. Having not managed to get back to my hotel beforehand, I was bothered I might be cold – but, unsolicited, a dish of hot coals was placed at my feet. A beer would have topped it all off, but “when in Rome” and all that…

The next day, I crossed the Ravi River to Lahore’s northwest to visit Shahdara Bagh and the mausoleums of the Mughal Emperor Jahangir, his wife Nur Jahan, and her brother Asif Khan, better known as the father of Mumtaz, the lady in whose honour the Taj Mahal was built. Here, once my tutktuk had left the manic chaos of the multi-laned highway beside the metro-bus terminal, was something more akin to rural Pakistan; I’d left the big city behind, at least for a few hours. Here were people’s lives – children playing in the street, a bicycle invisible under its massive load of bamboo, men walking home along the railway line – and deaths, a graveyard, cheek-by-jowl with life.

While Nur Jahan’s and Asif Khan’s tombs were in the middle of some much-needed work, Jahangir’s was, befittingly for the emperor, stunning. Featuring the same pieta dura work as the Taj Mahal (Jahangir’s successor, Shah Jahan, was responsible for both monuments), his tomb is housed in a large square building with minarets at each corner. Marble inlay decorates the red sandstone walls, whereas the minarets are themselves of marble, with geometric patterns in inlaid stone. When I returned to my boots – shed for the purpose of visiting the tomb itself – one of the guards pointed up with a questioning look. With the air of a Le Carré spy, checking over his shoulder, he escorted me round the corner and unlocked a door, motioning me in, up, and then further up. Barely one-person wide, the narrow staircase took me to the top of the minaret and a glorious view. Looking back towards Lahore, blue faded from the sky, killed off by pollution, but on my side of the river, the colours were fighting back.

My final stop was the Shalimar Gardens. I nearly didn’t go. Daylight was fading by the time I’d navigated my way there – tuktuk, metro-bus, and a second, much longer, tuktuk ride in what I presume was rush hour (aka even more insane traffic) – but the reward was enormous. Once again, Shah Jahan has left his mark in wonderful style. The gardens complex is vast, laid out geometrically in a series of terraces, each higher than the last. I trudged through the square gardens of the first terrace thinking blasphemously that it wasn’t anything special, particularly as the fountains and water features weren’t working, but then I reached the central level reserved for the emperor’s harem. And found myself in a Bollywood filmset, or so it felt. Below the marble balustrade at which I now stood, fountains teased the dying light, the colours of the sky reflected in the ornamental lake. A bridal party was having photographs taken on a marble platform in the centre. Kids played, couples courted, and Lahoris enjoyed a few minutes away from the hustle of life. I meandered around, hypnotised by the timeless beauty of my surroundings. Only the disappearance of the sun prompted me to more prosaic thoughts of my hotel and food.

That evening, I returned to the restaurant I’d eventually found my first night, and happily tucked into the best barbecued fish I think I’ve ever tasted.

The next day I was to head north to Islamabad up the N5, more romantically known as the Grand Trunk Road. Ending, as I’d started, with echoes of Kipling.