Planning a trip to Myanmar was like opening a box of chocolates. Where to start? With so much to see, it’s deliciously daunting, even with advice from a friend who’s been living there a while, though he readily admitted, “If a place is interesting, and has an airport within two hours’ drive, then I’ve probably visited. If it doesn’t, then I haven’t.” Right there is the second challenge: logistics. Roads aren’t great (66 km/41 miles in two hours is reasonable going, I was to discover within the first week), and, despite talk of improvements, the railways don’t appear to have been updated since they were first introduced in the 1870s. (I’ve seen references to the maximum speed being 24 kph/15 mph: they’re not going to rival the Shinkansen any time soon.) Even with the best part of six weeks and a following wind, I wasn’t going to be able to do anything like everything I wanted to, never mind factoring in the possibility that things might not go entirely as planned.

Mandalay was always going to be included, however, and it was my first stop after an acclimatising and sociable weekend in Yangon. It’s up there with Timbuktu, Samarkand, and, before I went to either, Bangkok and Peking (definitely this, rather than its current, spelling), for the sheer romance of its name. Yet I went prepared. I knew that the city had been devastated by Japanese air raids and that the Royal Palace had been burnt down as a result of British bombing. I wasn’t expecting much beyond the name, my first proper sight of the Irrawaddy River – another magical name (I’m ignoring the new spelling, Ayeyarwady) – and a convenient base from which to explore the local area.

It was also my third Burmese capital city in almost as many days. The Bamar monarchy believed in moving its capital on a regular basis, disassembling and moving key buildings from the old capital to the new one in an oddly nomadic fashion. Occasionally, as if running out of ideas, they’d go back to an old locale. The military government of recent times appeared to emulate this practice in the mid-1990s with the formation of Nay Pyi Daw, though indulged in a spate of new building rather than relocating buildings from Rangoon/Yangon. (Nay Pyi Daw was not on my list – “Milton Keynes without the roundabouts,” I was reliably informed.) Within a couple of hours’ drive of Mandalay, I would find myself in four more erstwhile capitals. So prolific are they in the fertile and slightly better climate of the upper Irrawaddy valley, I didn’t even realise that Amarapura – famous for its photogenic long teak bridge, rather than its history – had been a capital until after I got back to the hotel that evening.

Unusual in only having one name – despite the military’s spate of history-denying renaming in the late 1980s, many town and city names, like the country’s own name, continue to be used in both the old and new forms apparently interchangeably – Mandalay has remained Mandalay throughout. The centrepiece is still the old Palace, its moat-encircled red walls stretching an imposing couple of kilometres on each of its perfectly created four sides. While not quite being on a par with Beirut’s Corniche, the moat-side of the surrounding roads, being wide and tree-sheltered, is clearly popular with those “taking the air”, as well as running and exercising, using its intermittent collections of outdoor gym equipment with greater and lesser levels of expertise, though I’m not sure a longyi – the ubiquitous long skirt-like garb worn by men and women alike (but differently folded) – is necessarily the best workout clothing.

At the southeast corner, I was greeted with my first sight of Mandalay Hill, perfectly in line with the eastern Palace wall’s moat, and, from this angle, a perfect cone dotted with golden zedis (as stupas are known here). The next day I climbed its 1,729 steps (or so the Book tells me – I confess, I didn’t count). While this may sound a little daunting, the route is well broken up with un-stepped pathways and distractions, leading through so many shrines that shoes have to be left at the foot of the hill. What I wasn’t prepared for was the number of puppies. Stray dogs are prolific in Myanmar, but, somehow, they go in for having their puppies on Mandalay Hill. I swear, if that really cute one I fell in love with on the way up the hill had been in evidence on the way back down, I’d have been very hard pushed not to have the small fellow in my luggage right now. (Note to self: tell my nephew and niece not to come here. Jo had to be convinced not to send home every stray creature we found on our Central and South American peregrinations, whether feline, canine, simian or avian… and then there was the junior alpaca she met… A tale for another time.)

I was already clocking up a reasonable number of Burmese temples and beginning to get a flavour of the local form of Theravada Buddhism. I was conscious that the first week or so would only be a warm-up for the literally thousands of religious buildings waiting for me in Bagan, so tried not to overdo it. Glitz and gold are big here, dramatic at a distance but a touch overpowering up close after the first few. While many religious buildings are whitewashed stone or brick, there are a few surviving constructed out of teak, and this iconic old hardwood is a welcome contrast from the glitz. But there’s a nice harnessing of the modern to assist in bringing out the traditional: the Buddha’s aura is often illustrated with electric light, concentric circles of differently coloured cables of twinkling light that flash on and off in turn and/or at random. Occasionally, the aura’s rays are electrified instead, also in different colours and flashing. Sometimes women are forbidden from approaching the shrine itself: “Ladies Are Prohibited”, nice and straightforward, but this only applies at the last rail before the statue and offerings, so it doesn’t feel like too much of an exclusion. Shoes must be removed at the entrance to the temple grounds, an earlier point than anywhere else I’ve visited. Sometimes you are offered a plastic bag in which to carry your shoes; at other times you are forbidden from even carrying them into the temple; sometimes there’s a charge for leaving them in the care of someone; most of the time you just cross your fingers that they’ll be there when you come back. (Touching lots of wood, I’ve never had a problem… yet.) And it’s certainly not worth arguing the point – the English objections to this custom in the nineteenth century arguably contributed to one of that century’s three Anglo-Burmese wars.

Zedis often contain relics, but there are times when they are so prolific that I struggled to see their purpose. I’ve seen less crowded graveyards. Mandalay has a lovely couple of shrines – Sandamuni Paya and Kuthodaw Paya – where the surrounding zedis have been built in regimented lines and each, open-sided, contains a text-inscribed marble slab. This is reputedly the world’s largest book, the entirety of the Buddhist scriptures, the Tripitaka, engraved on over 2,500 slabs at the behest of the last Burmese king, Thebaw, who, by all accounts, would have been much happier remaining in his monastery rather being chosen to inherit the throne by a cabal of government officials and a scheming minor queen (though not his own mother) out of the 48 sons of the dying King Midon.

Sadly, the view from the top of Mandalay Hill wasn’t too impressive. The week that I was there the valley was still and overcast for most of each day. Even when the sun did make more of an effort, the haze didn’t entirely clear, so when I escaped the valley for the hills later in the week the sight of clear blue sky was most welcome.

Mandalay Palace was rebuilt in the 1990s with the use, allegedly, of forced labour. The Palace, though numbering about 40 buildings, is only a small part of the walled compound, the vast majority of which is off-limits to foreigners as it is still used by the military, a practice started by the British after they ousted Thebaw and his family, and continued by the Japanese during their occupation. I was rather taken aback to be greeted at the foreigners’ entrance gate with banner high on the Palace wall reading, “TATMADAW [the army] AND THE PEOPLE COOPERATE AND CRUSH ALL THOSE HARMING THE UNION”. (It’s not the place of this blog to make any political comment, so I’ll leave this one with you.) It’s odd to walk around the Palace, knowing that it is no more than a recreation of what was here before and, beyond the seven-tiered throne room, the effort seems half-hearted and the entire place feels forlorn. In my mind, I was trying to recreate an early scene in Amitav Ghosh’s wonderful “The Glass Palace” where the hero, little Rajkumar, joins the townspeople in running into the Palace immediately after the British victory to see what they can loot, but comes face-to-face with the fearsome yet impotent and pregnant Queen Supayalat. This general event happened – the townspeople overcoming their fear of the monarchy to satisfy their curiosity in the wake of the British victory, with the King and Queen then being whisked out of the Palace with their children in the back of ox carts on the first stage of their journey to what was to be exile in India – but I just couldn’t see it. The impersonality of the reconstruction, the overgrown paths outside, the lack of information about the various buildings: it seemed dead, fake, pointless.

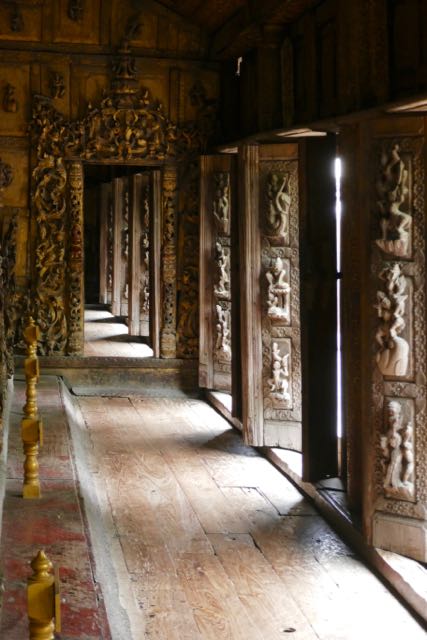

The contrast between this and the fabulous old teak originality of Shwenandaw Kyaung, the monastery that was next on my list that day, could not have been greater. Oddly, it had started life inside the Palace walls but, as it was reputedly the place where King Midon died, King Thebaw, feeling spooked by his father’s ghost, ordered it to be moved outside the Palace walls – and therefore it remained safe from the British bombing raids (and miraculously survived the Japanese onslaught).

A 45-minute drive down the road and a five-minute river crossing away is an erstwhile capital that had clearly been a popular choice. Inn Wa – or Inwa, also known historically as Ava – the city of gems, was the Burmese royal capital for much of the period from 1364 to the 1840s when Midon moved his capital to Mandalay and began that city’s short-lived role in history. It is picturesquely (and militarily sensibly) located between the Irrawaddy and one of its tributaries, with the remains of its city walls and moat punctuating the north-western corner of this land. Ordinary homes were built of wood, so they have not survived. The result, in common with other former towns and cities here, is a disproportionately concentrated collection of zedis, shrines and monasteries which, while in varying states of decrepitude, are nevertheless evocative and atmospheric. But the Inwa area is still occupied, and the religious monuments of yesteryear are interspersed with the homes and shops and businesses of several villages’ worth of people.

Wandering round Inwa for half a day was without doubt the highlight of my time in the area. For some reason that I can’t quite fathom, walking is not encouraged. “The” thing to do here is to hire a horse and cart, and there’s no shortage of both as soon as you step off the boat. “Walking not possible. Long way,” I was assured time and again by people who, let’s face it, had a commercial incentive in convincing me of the merits of their argument. Even once I was well on my way, I was invited time and again to board the back of a moped or a cart, whether or not that cart already had punters on board. And it wasn’t just the locals: “Get a horse!” hollered a middle-aged American from the back of his conveyance. Even the book I’m currently reading, Thant Myint-U’s fabulous “The River of Lost Footsteps” talks of how walking is dangerous because of snakes, though this may be a product of when he was writing: most of the roadways are surfaced nowadays, and the profusion of people and noise should put off all but the most audacious reptile. But the distances weren’t that great. I maybe clocked up 10-12 km (6¼-7½ miles) in my perambulations, if my phone is to be believed, and I was hugely rewarded by having the ability to stop when and where I wanted, to talk to locals and interact with kids (for the second time this week, a cute toddler blew me a kiss from the back of her mother’s moped), never mind the chance to visit temples that weren’t on The List, that I almost tripped over, and therefore had luxuriously to myself. When I got back to the boat drop-off/boarding point, I realised also quite how lucky I’d been in what I hadn’t realised was a comparatively early start. I may have crossed to Inwa at about 10.15am – not an early one even by my sleep-loving standards – but I had had the “ferry” to myself. Waiting to return four hours’ later, I saw the long-tailed boat full to the gunwales with maybe 20-25 people, both locals and tourists, bags and baggage. I was half-expecting a goat or hen to appear.

Sagaing (pronounced Sa-kai) was another homage to Amitav Ghosh. Without a hint of a plot spoiler, it’s a place that means something to one of the key characters in “The Glass Palace”, and I was intrigued to see its appeal. It claimed capital-city status initially in the fourteenth century, being the precursor in that role to Inwa, but it is better known now as a monastic centre. Its ridge of hills is positively peppered with gold zedis but, being now a little temple-ed out, I limited myself to two on this side of the river, one mega-glitzy and one renowned for its semi-circular colonnade of arches and Buddhas, and one on the Mandalay side, though I have to admit the latter’s appeal was primarily as a viewpoint for Sagaing and the two bridges. The original, the Ava Bridge, was destroyed by the retreating British Army as part of a scorched-earth policy in the face of the Japanese invasion, and not rebuilt until the mid-1950s, when it was for a long time the only bridge across the Irrawaddy. The second one, the Sagaing Bridge, was opened in 2008. In their proximity to each other, I found myself reminded of bridges much closer to home, across Scotland’s Firth of Forth, the newer of which I had yet to cross, yet I’d just been over each of these bridges on the Irrawaddy.

In an ideal world and with more time, I’d have wanted to take the train northwest of Mandalay, stopping at Pyin Oo Lwin, Hsipaw and Lashio, and crossing the Goktiek Viaduct. When constructed it was, at 318 feet, the second highest railway bridge in the world. As it was, on this trip at least, I had to satisfy myself with a day-trip to the old British summer capital, then called Maymyo, now renamed Pyin Oo Lwin (pronounced “Pyi-oo-lwi”). Myanmar is the land of public holidays – 27 a year, I’m told – and my trip coincided with the two this year to celebrate the Full Moon Day of Tazaugmone. This marks the end of the rainy season, and is the time during which monks are offered alms and new robes. I had already seen alms-gatherers a-plenty on the roads over the last week, usually accompanying a noisy truckload of people partying and blasting out music like a low-cost Mardi Gras float. (I found myself wondering irreverently if some people put money in the bowls to make the noise go away.) One of Pyin Oo Lwin’s temples, the Maha Aung Mye Bon Thar Pagoda, is particularly popular during this festival for the release of hot air balloons lit with candles, an offering to drive away evil spirits. Sure enough, we found the road to the temple already blocked off to traffic, even though we were well ahead of nightfall. Another feature of the festival is the making of new monks’ robes by way of weaving competitions that can last all night, commemorative of the Buddha’s mother staying up all night to weave robes for him. At Yangon’s Shwedagon Paya I’d seen a competition in full clickety-clacking force, and at the Maya Aung Mye Bon the looms were all set up for a competition that evening. The reward sounded extravagant – the joy of having a currency that’s about 1,350 to the dollar – but I felt sure that the successful participant would have earned every last kyat.

Earlier that day I’d had a welcome blast of nature and fresh air in the National Kandawagyi Gardens, another hangover from colonial times, now renovated and renamed, and opened by Senior General Than Shwe in 2001. Again, the holiday spirit – quite literally in some cases: the stall outside that sold me a can of iced coffee was selling far more alcoholic options than soft drinks – was very much in evidence. I was impressed to see someone set up a small drumkit, and spotted a couple of guitars around, although neither were in conjunction with the drumkit. I’m not green-fingered by any stretch of the imagination (the opposite, in fact, whatever that might be), but I do enjoy wandering around the product of someone else’s labour. However, for me, the Gardens’ highlight was mammalian. About halfway around the lake, I’d become aware of a whooping which was gradually getting louder. Given the alcohol and young people around, I had assumed the sound to be human in origin, but then I came across a group of people looking up into the trees. There I saw a simian mother and son, eastern hoolock gibbons, hooting at each other in the branches. Later, I saw a sole female watching the passing human traffic a touch lugubriously, seemingly entirely unfussed by the noise. I assume her offspring must have died; I couldn’t think of any other reason an adult female would be on her own. In the sound, I was reminded of howler monkeys, disembodied across the water when I was staying on Nicaragua’s Solentiname Islands. The hoolocks gave me a simply magical experience, and a nature highlight that I’m not expecting to better while I’m here.

Such, in a slightly large nutshell, was my few days in the Mandalay area. I could now almost justify a few days’ relaxation on the shores of Inle Lake before tackling the temple-a-thon that would be Bagan.